Dept of Culture

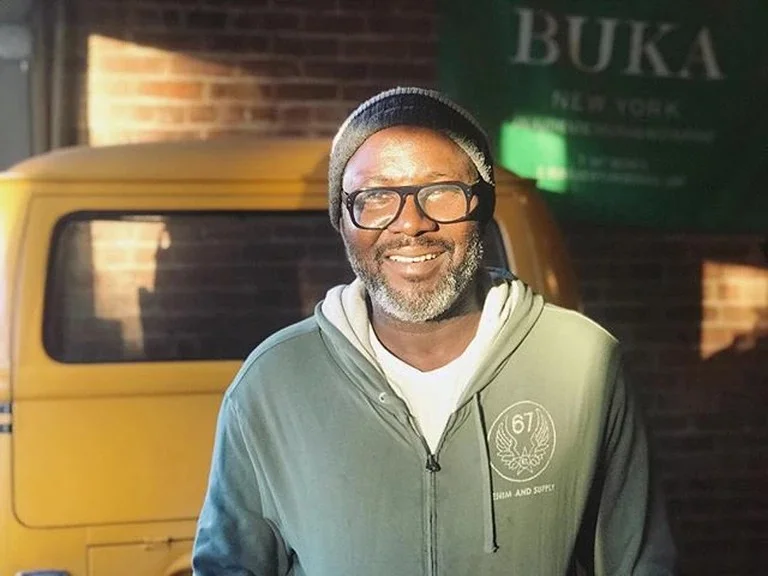

A 20-year veteran of the restaurant industry, Ayo Balogun has worked everywhere from a Michelin-starred Indian restaurant to an Italian deli making fresh mozzarella. He serves American food at his popular Brooklyn cafe, The Council Cafe, and offered similar fare at his now closed Trade Union Cafe. [Editor’s Note: Full disclosure; Ayo is also my cousin. -Tayo] But while he’d flirted with the idea of opening a place dedicated to his native Nigerian cuisine, he shied away from it.

“Nigerians can be difficult about restaurants because everybody says, ‘Oh, my grandmother can cook better than this,’’ Ayo jokes, explaining that, while Nigeria’s restaurant culture is newly burgeoning, most people eat at home. “I thought that if I did it, people would be critical.”

However, a series of Nigerian pop-up dinners that Ayo hosted called IYA EBA — a Yoruba name for women who sell eba, a West African staple food made from pounded cassava flour — proved immensely popular. This, coupled with an increasingly persistent inner call to do it for the culture, inspired him to start a new spot. Two weeks ago he opened the aptly named Dept of Culture, where he prepares elegant, flavorful four-course meals based on the regional cooking that he grew up with in Nigeria’s Kwara State. “It’s important for us to cook our own food,” says Ayo, 43. “We need to tell the story of our heritage. We need to celebrate our culture from our perspective. And we should do it with absolute dignity.”

“It’s important for us to cook our own food. We need to celebrate our culture from our perspective.”

At the Department of Culture, Ayo takes a fine dining approach to the traditional cuisine of north-central Nigeria. Open for dinner on Wednesday through Saturday, the Bed-Stuy BYOB, which seats just 16, is reservations-only. Ayo offers a four-course, pre-fixe tasting menu that changes frequently but sticks to ingredients similar to those found in Kwara State. In what feels a bit like dinner with a show, he emerges from the kitchen to present each dish, sharing details on their cultural significance. “There needs to be an element of confidence in our culture,” Ayo says of his decision to create a decidedly elevated experience. “Because I’ve never felt like any other country’s food is superior to what we do.”

On a recent Saturday night, we enjoyed a first course of hot, aromatic pepper soup with red snapper. Course two: a vegan take on suya, a popular Nigerian street food, made with spice-sprinkled mushrooms instead of skewered meat. A dish of pounded yam topped with spinach, striped bass and tomato-and-red-pepper-based obe sauce came next, followed by a dessert of caramelized dodo (sweet plantain) with vanilla ice cream. Other dishes offered among Dept of Culture’s constantly rotating menu include octopus suya, egusi (melon seed) stew with pounded yam, and tangy Nigerian cheese curds called wara.

“I want to present Nigerian food differently,” says Ayo, who imbues the work with deep meaning. “Whatever we do as Africans, it's not only for us. It's for all Black people across the Diaspora — this is their heritage too.

With just 16 seats, spread across one large wooden table and a dusky pink counter, Dept of Culture is small and communal, just as Ayo intended. In addition to introducing people to hyper-regional Nigerian cooking, at the restaurant he also fosters conversation and connection in the intimate setting.

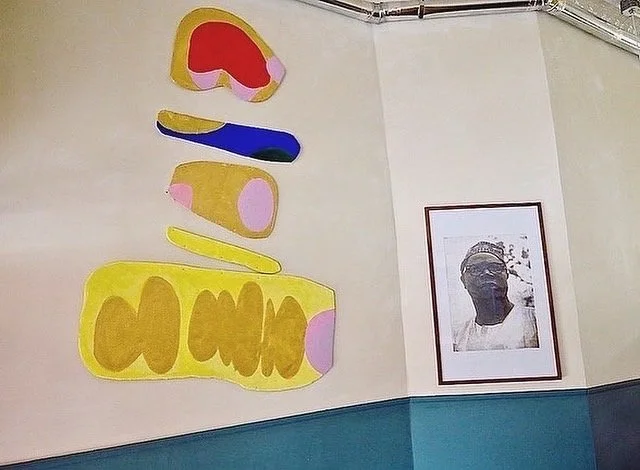

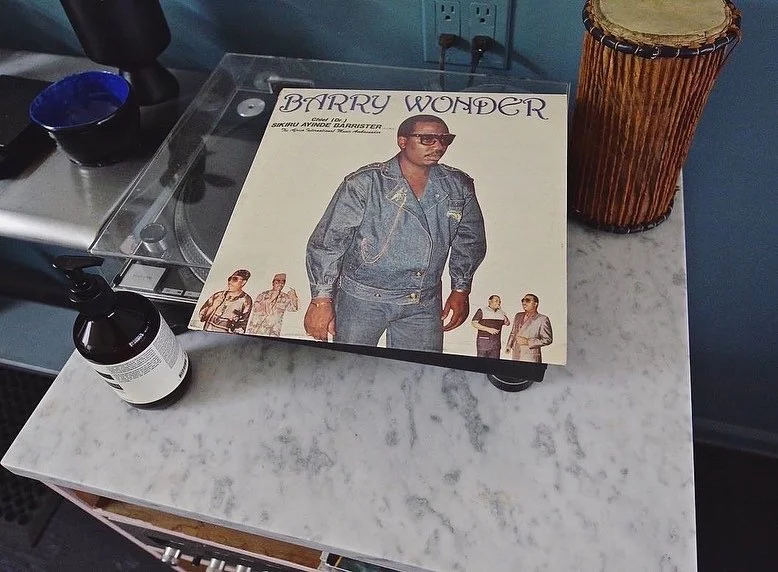

“I wanted an open kitchen, so it feels like somebody’s coming to visit you,” says Ayo, who has further cultivated homelike vibes by lining walls with family photos, notably a portrait of his beloved grandmother, Ayinke, who taught him how to cook as a child. A record player spins old records by Nigerian jùjú legends, the music he grew up listening to at home. “When I told people I was gonna build a Nigerian place, a lot of my friends were like, ‘Are you gonna put, like, baskets on the wall?’” Ayo says with a laugh. “I love the look of woven baskets, but that wasn’t what I saw growing up.”

While the culinary point of view at Dept of Culture is a departure from his other restaurants, which have focused on American comfort food, Ayo’s business ethos is the same. “When we opened Civil Service and Trade Union, the thought was for the thing to have way more meaning than just financial,” says Ayo, who has helped guide other Nigerian business owners, including the teams behind Brooklyn Suya and Brooklyn Kettle.

“There’s a way that we can build community and bring each other up through business. At the end of the day, the way I look at my wealth, it’s measured through their success. It gives me a sense of joy to know that I’m part of that collective journey.”

327 Nostrand Ave., Brooklyn, deptofculturebk.com