Origins of AfroPunk

Here in the stolen summer of COVID, Brooklyn has been paused, distanced and canceled. We’re massaging sanitizer into hands that previously held passes to our favorite summer tentpole events, and, since it’s August, right about now that would mean the Afropunk Festival. The festival’s ascension from humble beginnings to global brand is truly a Brooklyn story that begins with James Spooner’s seminal “Afro-Punk” film and the vision he created with partner Matthew Morgan.

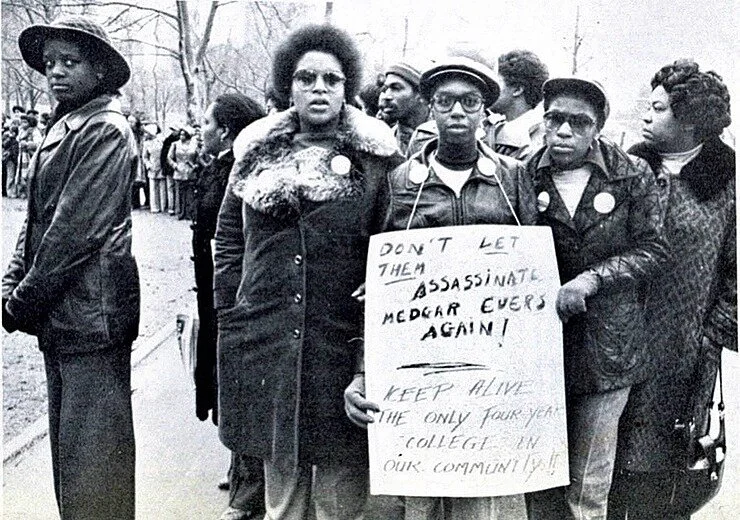

Afropunk the festival was originally based on Spooner’s 2003 documentary: a DIY examination of the African-American experience in the white punk rock world. While youth culture often serves as a community offering solace and validation, that wasn’t always the case for Black kids into punk rock. Spooner’s film captured their alienation and cultural “othering” within the scene.

⠀

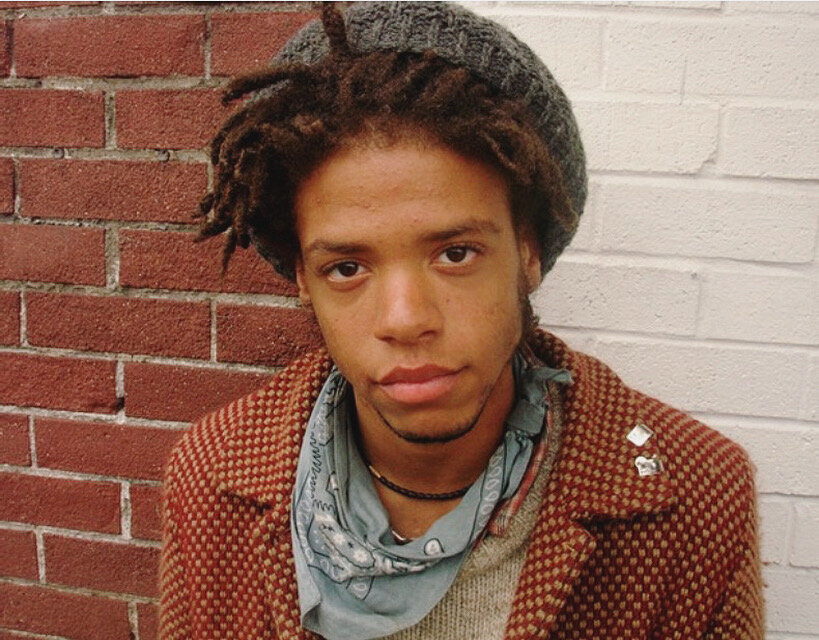

These were feelings Spooner knew all too well, having grown up in the predominantly white community of Apple Valley, California, before moving to gentrifying Williamsburg, Brooklyn. In 2001, at age 25, he moved to Crown Heights to sate his need for Black community — then set off across the country to shoot his film. “When I started the film, I was kind of buying into what had been told to me by Black mainstream people my whole life: ‘You're trying to be white,’” Spooner says. “As I was making the movie, I was finding out for myself that my experience as a Black person was a valid Black experience.”

Ed Marshall

“As I was making the movie, I was finding out for myself that my experience as a Black person was a valid Black experience.”

Ed Marshall

Jeffrey Wright

James Spooner

James Spooner

Mathew Morgan

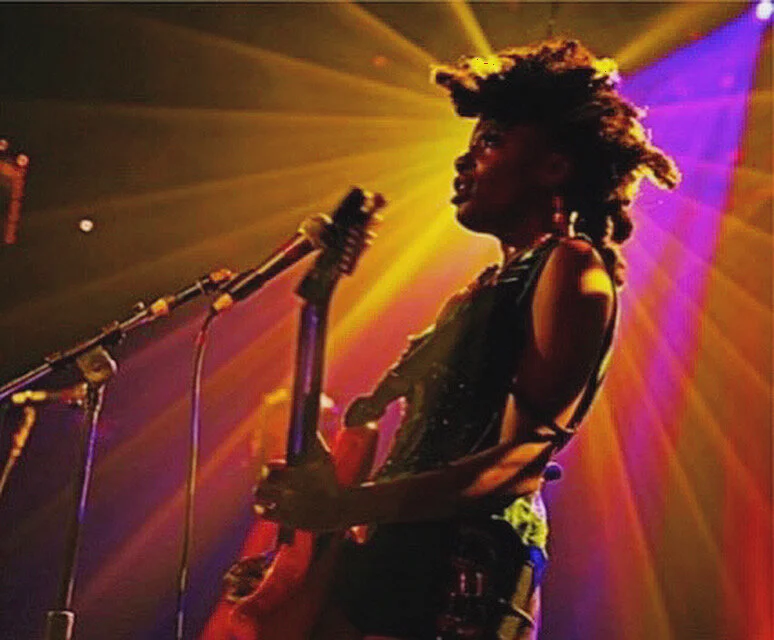

The success of the “Afro-Punk” film led Spooner to music manager Matthew Morgan, who was struggling to get his left-of-center music acts signed to major label recording contracts. This was particularly true for Morgan’s client Stiffed, a punk band fronted by Santi White, who went on to perform as the critically acclaimed Santigold. Their idea was to create a performance platform showing record labels there was an audience for the music.

⠀

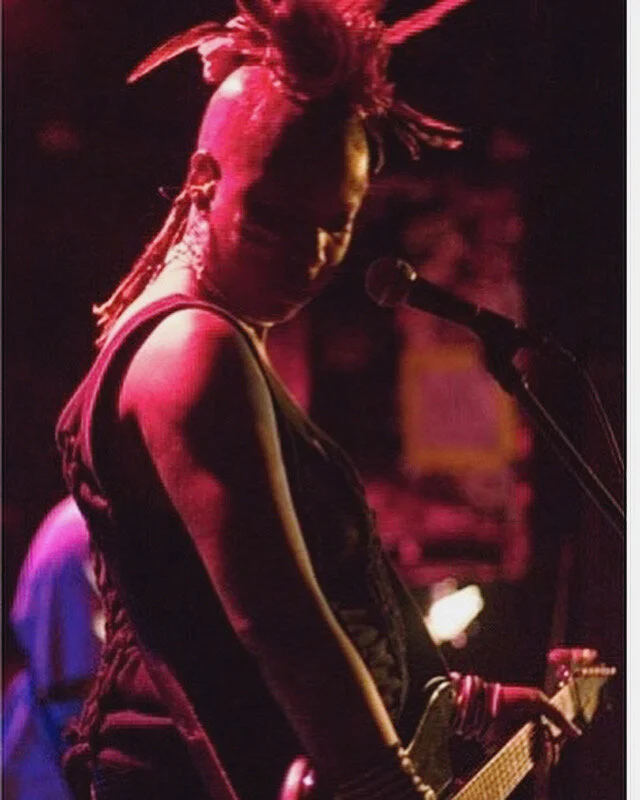

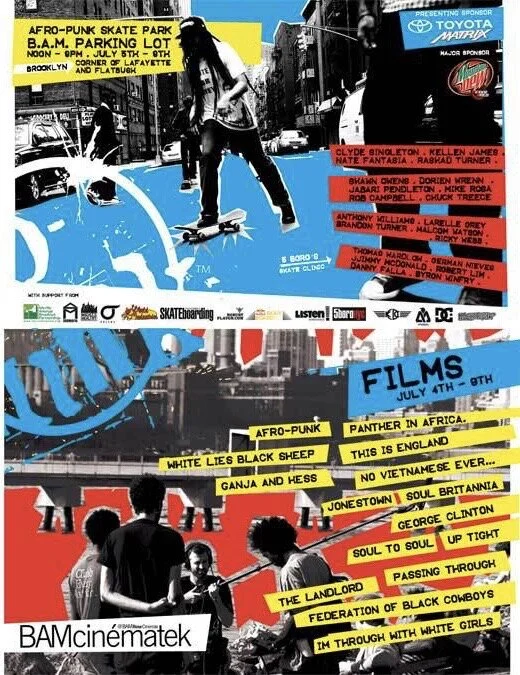

With that in mind, Spooner and Morgan initially produced a series of live shows called the Liberation Sessions where they screened the “Afro-Punk” film and put bands on stage at The Delancey in Manhattan. Packed houses ensued. They eventually parlayed that energy to the Afropunk Film Festival, a thematic weekend of films held at the BAM by day and a series of live shows across New York City at night. In 2005 they persuaded BAM to give them space for the first self-contained Afropunk Festival, which would feature acts including Living Colour, Saul Williams, Tamar-kali, Cipher and Honeychild Coleman.

⠀

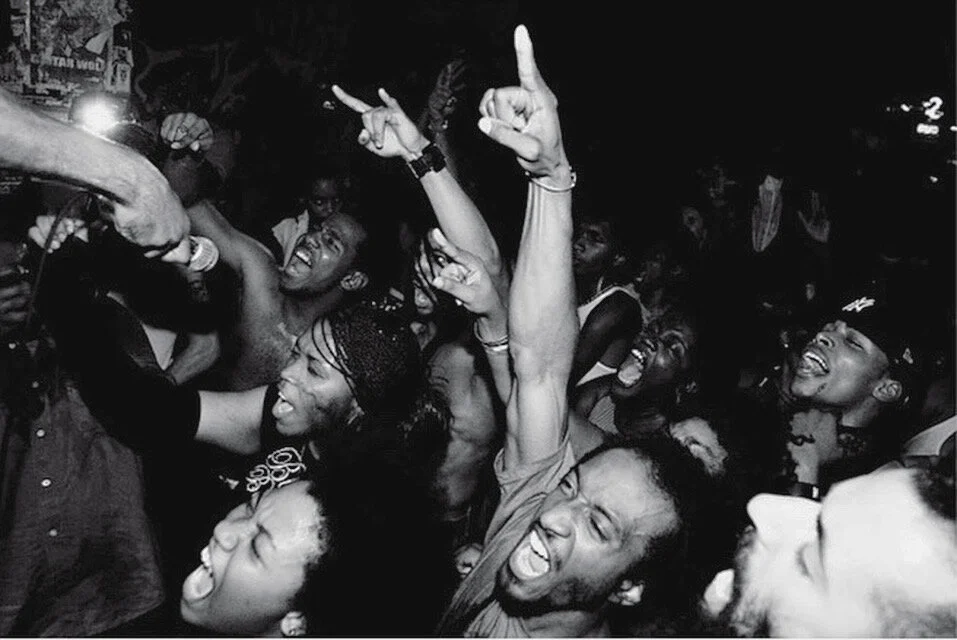

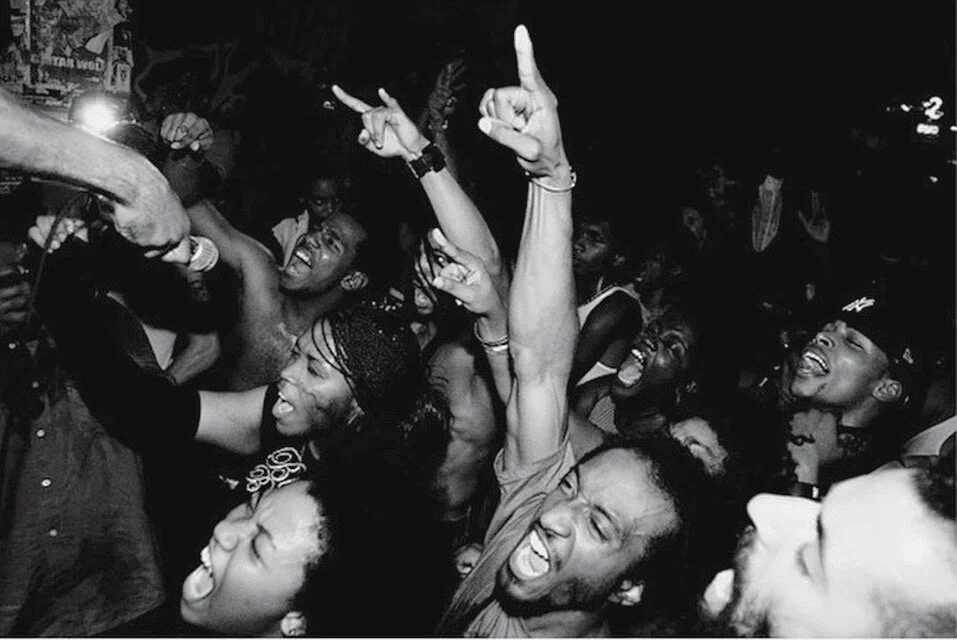

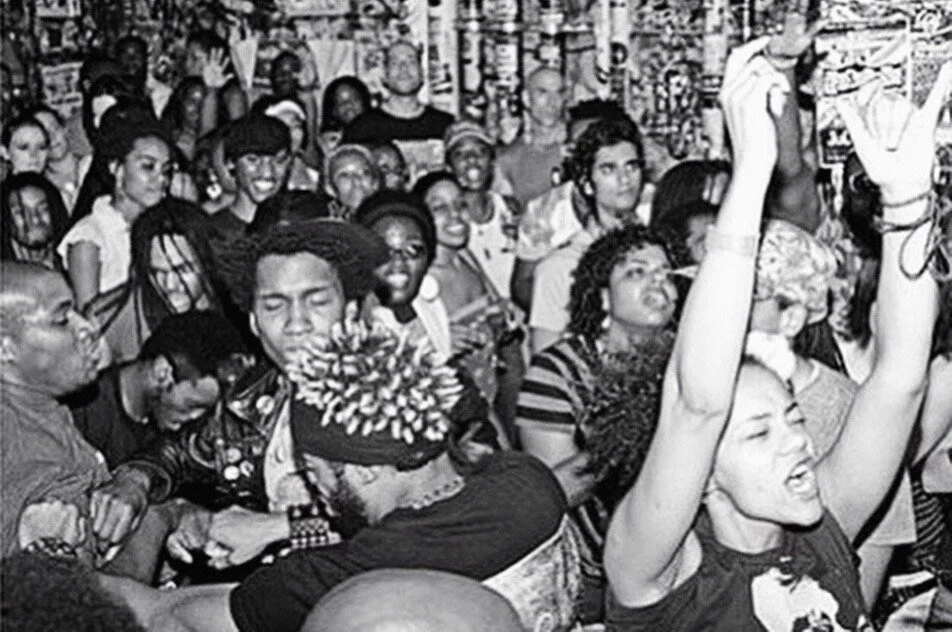

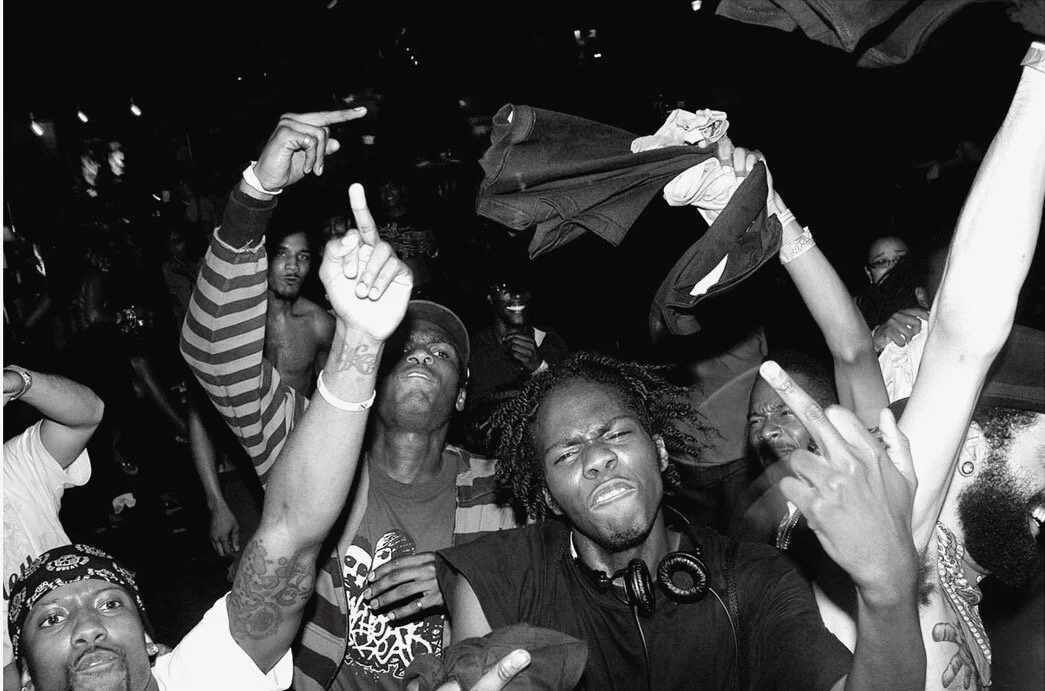

Those early festivals, from 2005-2008, found Spooner and Morgan changing the rules of cultural and musical engagement when it came to the young, gifted and Black. The BAM parking lot, for example, was replete with skateboard and BMX ramps. “Creating a space where Black kids can free themselves enough to explore whatever they wanted — however they wanted to dress, however they wanted to dance, however they wanted to eat, however you wanted to express yourself,” says Morgan. “For me, that was purely about Blackness.”

Bashira Webb

Jeffrey Wright

Bashira Webb

Bashira Webb

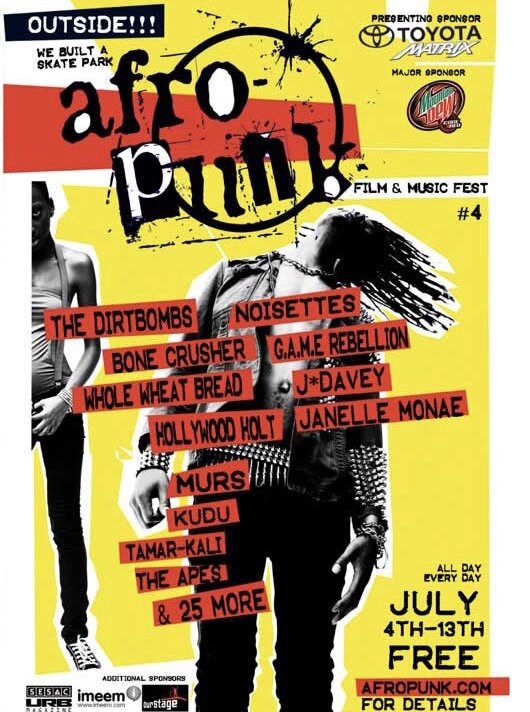

By the fourth Afropunk Festival at BAM in 2008, Mountain Dew and Toyota came on as its first-ever sponsors, making everything feel bigger. I remember the rap-rock band Game Rebellion killing their live shows in those times. Netic Rebel, frontman for the group, said, “In the early days of Afropunk, it was super special and super important. Afropunk legitimized the bands that it loved, and the bands legitimized Afropunk.”

In Brooklyn, we embrace beautiful occasions like rooftop parties, street fairs and outdoor concerts as a quid pro quo for a winter of cold-ass commutes and heat-hoarding landlords. The original Afropunk gave us an amazing block party in Clinton Hill and free live performances in Fort Greene Park that were small in size but didn’t stop bands, from The Noisettes to The Dirtbombs, from ripping the show to pieces.

Many folks only know about the contemporary Afropunk in Brooklyn’s Commodore Barry Park, where superstars such as Lenny Kravitz, Grace Jones and Lauryn Hill have rocked the stages, with global offshoots in Brazil, South Africa and Paris. The festival turns 15 in this pandemic summer of 2020, which, anthropomorphically, would make it a petulant teenager. But when that first festival dropped down in pre-gentrified Fort Greene, it was a wonderment that grew beyond punk rock, creating a Black cultural experience that, for so many of us, felt like home. —Dick Burroughs